Published Works

A JOURNEY THROUGH LEAFSCAPE

Although its geographical form and dimensions are neither apparent nor understood, the quixotic land of Leafscape can be reached via many portals. You can find them anywhere if you know where to look. I know for example, that they exist within the Victorian suburbs of London and in the dusty olive groves of Andalucía, Spain; Over time, I have inadvertently stepped through them on more occasions than I care to count.

My first journey into Leafscape’s otherworldly realm happened one warm afternoon in a busy part of London’s east end. I had already covered large expanses of this urban terrain on foot, often following imaginary straight lines that I would draw on old maps. I had always thought of London as a city made up of angles and of sharply defined divisions and contrasts.

After years of tracing lines through this city and experiencing the resulting abstract patterns, I decided that perhaps I should leave London and its urban delineations and find somewhere with more diverse and contrasting qualities. After a certain amount of deliberation and focused pragmatism, I set out for the barren open vegas of Andalucía. I packed my Dr Marten boots, placed my life of maps and straight lines into neat little boxes and began saying my goodbyes to a city and its inhabitants from which I had constructed such a rectilinear world.

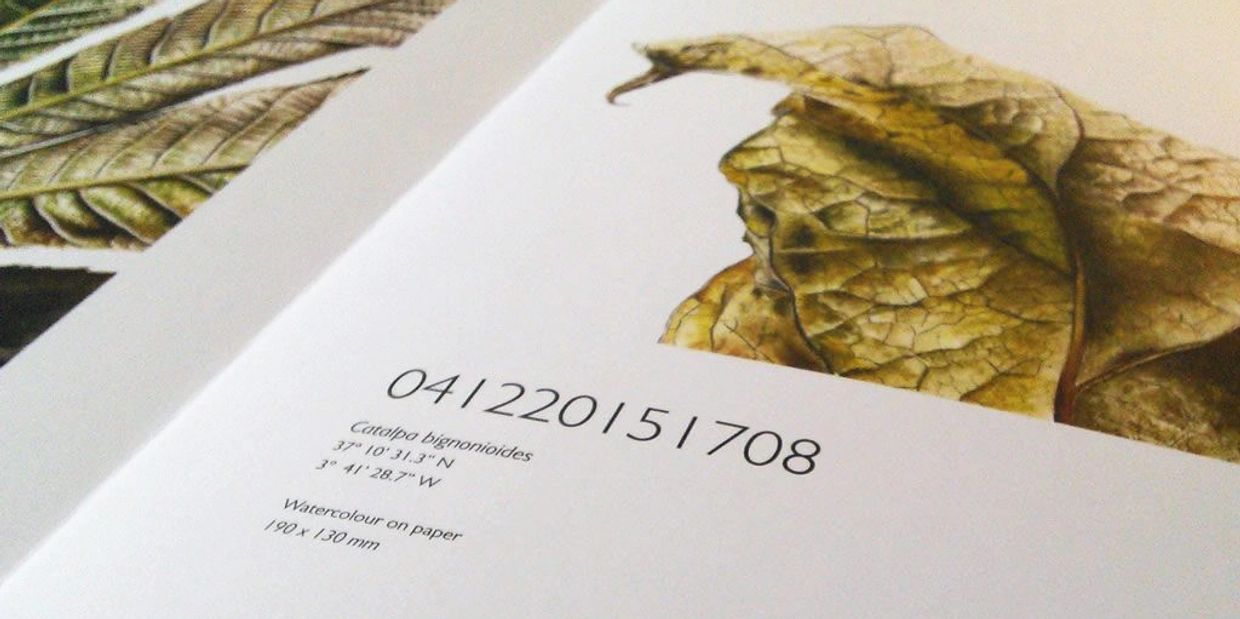

On that warm afternoon, shortly before my departure, as I walked towards Brick Lane something on the pavement caught my eye. Carried on a summer breeze and gliding rapidly above the paving stones, it was abruptly brought to a halt by my feet. Crouching down I picked up the leaf. Looking upwards I guessed that this heart-shaped form had fallen from the large catalpa tree at the end of the road. It was bruised, city-beaten and covered in rips and tears and I identified with it immediately. That’s when I entered the portal. In the blink of an eye I glimpsed inside Leafscape. The catalpa leaf showed me what was on the other side of those straight unforgiving lines and no sooner had I seen it than it was gone. This was my first experience of a portal. It was momentary; but you never forget your first time. Without hesitation I took the leaf back home with me. It was large; 30cm at its widest point. I began to paint it and a process of documentation was initiated.

After rendering its external appearance, I pressed the leaf so I could finish working on it when I got to Spain. I found I wanted to capture every scratch and hole; the marks and vicissitudes of a life lived in Leafscape, so I magnified the drawing to make it considerably larger than reality. I decided that I had to leave out the restraining edges in the composition because otherwise I couldn’t fit the whole leaf into view. Visually, I rather liked the effect it gave. Furthermore, it felt like that catalpa leaf had for the second time drawn me into another world, both of us trapped in time and space, our extremities defined by the frames of our ethereal existence. We were lost in this part of Leafscape for forty weeks.

Once in Andalucía, I firmly established the habit of a daily walk which would take me in a loop around the agricultural plains near my village. I say ‘loop’ because in contrast to London my walks here were always circuitous, never linear.

On one of these circuits, as I made my way past a field of noisy goats and their clanging bells, I noticed a farmer had placed a handmade sign in his artichoke field on the other side of the path. On it, using a thick, black pen, he had written ‘¡¡Cuidado Veneno Peligroso!!’ (Caution, Dangerous Poison). I immediately thought it absurd to label a food item as poisonous, but then everything is illogical in Leafscape. I promptly entered the field and painted an artichoke leaf under a big, blue sky. The leaves of the artichoke took on a menacing reptilian appearance in the bright Spanish light, an aspect that I found myself accentuating in paint.

As the seasons changed, the leaves from another catalpa tree began to fall onto my lawn, as they became separated from their host by a scorching Andalucían sun. The tree, which seemed more healthy and vibrant than the sickly specimen in Brick Lane, had started to shed its huge heart shaped leaves in June. I would sit and watch them drop from the canopy like giant, green, silken handkerchiefs until they reached the parched lawn where they would cook like poppadoms in a frying pan. Crispy and perfectly preserved in a range of hues, these leaves mesmerised me, for I could sit and paint them for hours and they would not move nor discolour. I painted nine catalpa leaves in Leafscape.

At approximately the half way point, my circular walking route would take me through several densely-planted poplar woods. These plantations are the closest thing I have to real woodland in Andalucía and they were where I went to sit and reflect. They grow poplar here as a crop for making things like match sticks, telegraph poles and maybe even artist’s board. When I wander these green corridors. I always think about how many of the great Renaissance painters worked on poplar.

The farmers here water their crops using an old irrigation system dating back to the Moors, who repaired and improved upon the original Roman systems that had fallen into disrepair when they ruled these lands. Every field and plantation is covered with a network of shallow trenches which, at different times of day depending on which sluice gates are opened or closed, direct water from the Sierras to the crops.

The poplar woods always look more impressive after they’ve been watered. The lake of water that collects around the roots reflects the canopies like a giant, glassy mirror. At this point it is difficult to tell up from down, earth from sky or reality from fantasy. It was evident that there was something about this part of Leafscape that, like my walk, looped. As often as not I stepped through a portal, for there were many here. Sometimes I didn’t even realise I was doing it. I would return to the same spot time after time. In the course of a year I brought back five leaves. I still cherish these woods today.

There’s a section of my walk where the mud path bridges over the Moorish watercourses before bending sharply to the left. Here, the fields of garlic arch rhythmically towards the road and somewhere in the distance, those rows of tall poplar trees can be seen reaching for the sky. When I walk around that corner I always feel like I am standing in the middle of a van Gogh painting. Just before this corner begins, there are two enormous Mulberry trees which grow either side of a farmyard gate, marking the entrance to Leafscape. They must be approximately 200 years old, covering the road in dark red berries during the summer. It was from underneath these trees where I entered Leafscape 040420161613.

One day I returned from a walk and found a bright yellow ginkgo leaf on my doorstep. This was strange as I hadn’t seen any ginkgo trees in the area. I cautiously picked it up and returned to Leafscape. Several months later I found the ginkgo trees. They were a mile away in some municipal gardens and their leaves were a lively green. I preferred them yellow.

I made occasional trips back to London and made further discoveries. In a secret spot at the back of the Chelsea Arts Club there is a garden and inside this garden there is a tiny pond and in this tiny pond there is a gunnera and within this gunnera is a portal. You can’t miss it, unless of course you happen to visit in the winter. This was the most complicated leaf I painted, for the sun shone through it like it shines through a stained-glass window. There were so many rivulets and spikes. Much to my chagrin, I had to finish this piece back in Andalucía using photographs but I was determined to capture it because it had come from one of those hard to reach places in Leafscape; a place where a secret key was needed to gain access.

On a particularly sunny day in Hyde Park I located my first and only large oak leaf. Someone had snapped a branch from one of the smaller saplings and the leaves had dried in almost the same way as they did in Spain. Semi-preserved, I took the leaf with me to Bognor Regis where I traced its curves with a wetter brush than I would have used in Spain. It’s often wetter in England, even in Leafscape.

I revisited Leafscape many times after the adventure in Hyde Park, mapping its new territories each time. However quite suddenly after months of travelling, I reached what appeared to be its end. The portals to Leafscape were becoming increasingly difficult to find; sometimes they’d just move or they would disappear altogether. I found myself walking in circles in London, a place where I had previously walked in straight lines and so I began to wonder if Leafscape had just been illusion all along. It seemed so; after all, everything mirrored and looped in this fractal world, to the point that my journey was ending in almost the same way as it had started.

However, just when I thought I’d reached the boundary, I discovered a new, shiny and incandescent portal on rose bush and with that I soon found another, this time in the judas tree where I had found another gateway 18 months previously. As I entered Leafscape on these last occasions I was beginning to notice that everything was either fading or glowing. Lines were becoming difficult to follow, time was slipping through my fingers and the colours of its contours where being washed out by white. The intensity of this light was so harsh, that I could not even record my last journeys through Leafscape for I could not see where I was going; I could only hear its echo.

Although its geographical form and dimensions are neither apparent nor understood, the quixotic land of Leafscape can be reached via many portals. You can find them anywhere if you know where to look. I know for example, that they exist within the Victorian suburbs of London and in the dusty olive groves of Andalucía, Spain; Over time, I have inadvertently stepped through them on more occasions than I care to count..

Published Works II

THOUGHT SURVIVES

It has been 60 years since Yves Klein painted 11 identical blue canvases for his ‘Proposte Monocrome, Epoca Blu’ at the Gallery Apollinaire. For this exhibition, each canvas was painted with an ultramarine pigment which was suspended in a synthetic resin thatwould retain the brilliancy of the blue. This was the start of the colour: International Klein Blue. For Klein there was no other colour that described the infinite better. Three years later, Klein created his performance piece “The Newspaper of a Single Day”, where he distributed copies of his own newspaper in Parisian kiosks for one day only. It was a ground breaking moment, no artist had done this before. On the first page, a photograph of the ‘Leap into the void is titled: “A man in space!”. It seems, for Klein there was little else more exciting than the infinite, the colour blue and the sky.

Please leave me alone; let me go on to the stars. - Arthur C. Clarke

Seventeen years after Yves published his ‘Leap into the Void’, Voyager 2 was launched on an exploratory mission to find and record the planet Neptune. Twelve years later, after having explored Uranus, it reached the blue ice giant and a series of blue photographs were sent back to Earth – it was another one of those ground breaking moments. Our first glimpse of Neptune. But Voyager’s story didn’t end there. Its mission having been extended, Voyager 2 is now finds itself over 13 billion miles away from its home planet, exploring interstellar space. Like Yves, it is travelling through the void, observing the infinite.

Fixed to the side of Voyager 2 and its twin Voyager 1, are two Golden Records. Each copper phonogram was made in case a Voyager came into contact with extraterrestrial life and was carefully curated to portray the true diversity of life and culture on Earth. On the recordthere is a variety of natural sounds, such as those made by the sea,the weather and animals, including the songs of birds and whales. The record additionally features music from different cultures over the decades, spoken greetings in 59 different languages, the sounds of footsteps and laughter and the brain waves of a young women in love. For me, the production of this record and its subsequent attachment to this spacecraft is a celebration of the both optimism and altruism of mankind; of our enduring belief that we might find life elsewhere and that we aren’t completely alone.

When Voyager 2 completed its exploratory mission and took the last photograph of Neptune back in 1989, the cameras needed to be switched off to conserve energy. But astronomer, Carl Sagan, had the romantic idea of turning the spacecraft around to take one final photograph of our planet Earth, one blue planet as seen from another. Objections were raised by NASA as from so great a distance the resulting image would have no scientific value, but Sagan could see the poetic potential of such an image and after much persuading, he was eventually granted permission. What we are left with is an image of a fuzzy, minescle, pale blue dot suspended alone in a dark, black void.

The universe is said to be so unimaginably large because Mankind exists and the western idea that the world would go on without us being here could in fact be incorrect. For example, we could never prove it existed without us being in it. This, in simple terms, is Heisenbergs’ Uncertainty Principle, which suggests that nothing can be said to exist until it is observed. The observer is the participator and we are part of the illusionary performance. Even color is an illusion created by our brains.

What we call art - painting, sculpture, writing, music – is also illusionary. That is, art is employed as a ritual to produce certain effects. Like a magician, the artist is trying to make something happen in the mind of the observer or participator. All art is a performance, a ceremony, as a means not to attain a belief, but rather a way to guide the audience and artist through a portal that allows them to reach abstraction, so that they may transcend and return a new.

The world is certainly what we make of it. How we observe it and how we participate in it. INKQ is a composite stage where artists, scientists, philosophers and historians can participate, exploring their ideas in a space without boundaries, without convention. This could be a ground breaking moment, as with all things, we don’t yet know. Like Yves and Voyagers 1 and 2, we are taking the leap. Thank youfor being on this journey with us.

"Sometimes ideas, like men, jump up and say ‘hello’. They introduce themselves, these ideas, with words.Are they words? These ideas speak so strangely. All that we see in this world is based on someone’s ideas. Some ideas are destructive,some are constructive. Some ideas can arrive in the form of a dream. I can say it again:some ideas arrive in the form of a dream." - The Log Lady

Casa de la Morera, Estudio de Inky Leaves, Calle Cadiz, Albuñuelas, Granada, 18659, España

Estudio: www.casadelamorera.com